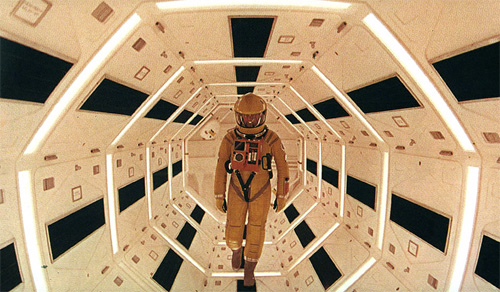

Welcome to the Geek’s Guide to Classical Music! Being a musician and music educator by trade, and also a bit of a sci fi geek, I present here the first in a series of articles exploring classical music used in the context of science fiction movies, including background information about composers, instruments, and sometimes highlighting specific movies as well. Even if you know nothing about classical music, you have heard it on both big and small screens. My goal is to help you identify famous works and composers and give you some “fun facts” about them, not to bore you, so have no fear. For this first installment of the GGCM, let’s take a look at one of the most famous sci fi movies of all time, which also happens to have a famous classical score: Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

It’s one of the most famous pieces in sci fi movie history — the opening music, starting with a simple series of notes that builds in volume to two huge chords played by the whole orchestra. Next is the two-pitched, low beat of the timpani, or kettle drums, followed by two repeats of the same sequence, only with different chords at the end each time. The last time through leads into the triumphant fanfare that accompanies the rising of the sun behind the moon and the display of the movie’s title. We hear it again at several other crucial points in the movie as well. It is “Sunrise,” the opening section of a larger work entitled Also Sprach Zarathustra, written by German composer Richard Strauss (1864-1949). As a matter of fact, most people refer to it simply as Also Sprach Zarathustra (or its English translation, “Thus Spake Zarathustra”) because it is the only part of the larger work that anyone ever hears.

Strauss is most famous for writing operas and symphonic poems (also called tone poems), which are works for orchestra in which the music tells a story or portrays particular scenes, much like a movie soundtrack does. One of his more famous ones is Don Quixote, a musical illustration of the Cervantes story, but Also Sprach Zarathustra falls into this category as well. It is based on a philosophical treatise by Friedrich Nietzsche written from the point of view of the fictional prophet Zarathustra. The nine sections (the musical term for them is “movements”) take their titles from selected chapters of the book, of which “Sunrise” is the first.

Not to be confused with Richard Strauss is Johann Strauss, Jr. (1825-1899), commonly known as the “Waltz King.” His was a very musical family — his father and several of his brothers were also professional musicians. Although his father tried to discourage him from studying music, Strauss followed in his footsteps and became famous in Vienna as a composer of waltzes and other dance music and as the leader of an orchestra that played for balls all over Vienna, including at the imperial court of Austria-Hungary. On the Beautiful Blue Danube, or simply, The Blue Danube, is his most famous waltz, and it is heard frequently in movies, television, and commercials. In 2001, it accompanies the scene where the shuttle is docking with the space station:

If the music you are hearing is not one of the two pieces already mentioned, then you are hearing something by avant-garde 20th Century composer Gyorgy Ligeti (1923-2006). Born to a Hungarian Jewish family in Romania, Ligeti’s music studies were cut short by World War II, when he was sent to a labor camp. Other family members were not so lucky — both his father and brother died in concentration camps, although his mother did manage to survive Auschwitz. After the war he continued his music study and worked as a composer and teacher, eventually becoming an Austrian citizen after escaping Communist rule in Hungary and living in Austria and Germany for the rest of his life.

Ligeti’s work encompasses all types of compositions, from orchestral works to keyboard pieces to choral and vocal works, including a Requiem, the musical setting of the Catholic funeral mass. Although his pieces represent an eclectic mix of musical styles, the four represented in 2001 share his characteristic focus on pure sound and the way different instruments and voices can be combined to create different sounds. This focus on sound clusters rather than on rhythm, melody, or harmony lends itself well to the otherworldly scenes Kubrick creates. In the movie you can hear Atmospheres, Lux Aeterna (“Eternal Light”), Adventures, and the “Kyrie” section of the aforementioned Requiem, which is the music that accompanies the astronauts when they first encounter the monolith on the moon:

I hope you have enjoyed this brief survey, and more importantly, that you have learned something! Tune in next time for a close-up of the great German composer Ludwig van Beethoven and a look at some of his famous works that you probably have heard before. (Hint: We’ll be encountering Stanley Kubrick again.) Please feel free to leave a comment with any questions you may have, as well as suggestions for future installments — is there a piece you’ve heard in a movie that I can help you identify, for example? Thanks for listening — class dismissed!

I might mention that another classical work featured in “2001” is the Adagio from the ballet “Gayane” by Aram Khatchaturian, heard in the first two sequences onboard “Discovery.”

One of the reasons I think these classical works are so well integrated into the framework of this epic film is the way they are used–not for decorative purposes so much as to be part of the intellectual drive of the story. In that sense, it’s not surprising that the opening of “Also Sprach Zarathustra” was so cagily utilized by Kubrick to signal an evolutionary step forward in Mankind’s existence. But what struck some people funny back in 1968, and might still even to this day, is how “The Blue Danube” is utilized for the space docking sequence. Only Kubrick, it would seem, would have the nerve to do it that way with that most popular of all waltzes. But then again, it is an interstellar ballet of sorts.

Thanks for this look.