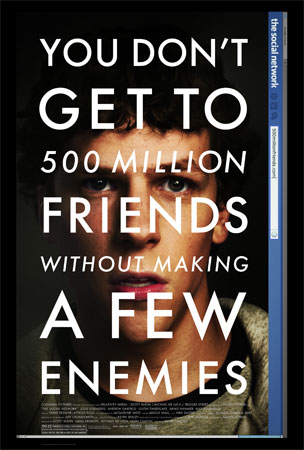

Director: David Fincher

Screenplay: Aaron Sorkin

Cast: Jesse Eisenberg, Justin Timberlake, Andrew Garfield, Josh Pence, Armie Hammer, Max Minghella

Rated: PG-13

“You’re not an a**hole, Mark, you’re just trying to be.”

Watching this film reminded me of the famous passage from the Gospel According to Mark that asks, “What good is it for a man to gain the world and lose his own soul?” Believe me, the irony isn’t lost on me that such a passage would be attributed to a man named Mark and be so spot-on to this film’s story.

I rolled my eyes when I first saw a trailer for this. I thought, “Great–‘Facebook the Movie.'” At the time, the very thought of it to me stood as a testament to how huge a part of our lives one social networking site has become. For many people, it’s the first thing they look at in the morning. For others, it keeps track of their social life, from dating to friends’ lives to upcoming events. Still more people use it to raise fictional cows and pigs. Facebook has become so huge we forget how it started–in a dorm room at Harvard.

What really began to change my mind about this film was a combination of things. Executive Producer? Kevin Spacey. Director? David Fincher. Screenwriter? Aaron Sorkin. Further, as a law student, the film’s issues of Intellectual Property law called me to analyze them. (Author’s Note: If you ever go to law school, you’ll eventually discover that you can’t help but analyze legal issues in everything–even if they aren’t there.)

Based on the nonfiction novel The Accidental Billionaires, the story of Facebook starts with a girl. In Citizen Kane-like fashion, the website takes off after Mark Zuckerberg (Zombieland’s Jesse Eisenberg) goes on an alcohol-fueled rant about the girl who just broke up with him. In succession, he says hurtful things about her on his blog, then creates a website to compare girls on Harvard’s campus that ends up crashing the network. This brings the attention of Divya Narendra and the Vinklevoss brothers who recruit him to build their own social networking site. With the financial assistance of roommate Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield), Zuckerberg gives the preppy students the run-around and creates his own site “The Facebook.” Like most internet phenomena, it ends up taking off faster than anyone could have predicted, and certainly brings more attention and responsibilities to its creator than he could truly handle.

It is at this point that Napster-creator Sean Parker (Justin Timberlake) enters the picture to play the devil on Zuckerberg’s shoulder. While Eduardo wants to start generating profit through advertising, Parker sweet talks Zuckerberg with the fame and fortune Parker has earned from his online endeavors. Zuckerberg is blinded by the cult of personality, and we the audience are shown what Parker’s life is truly like–broke, paranoid, and crashing in coed’s beds. He slowly-but-surely pervades Zuckerberg’s life and muscles Eduardo out, leading to the lawsuit that becomes the frame for the film’s plot.

As for the website’s notorious founder, throughout the story, Mark Zuckerberg comes nowhere close to being portrayed as a saint. From the very first scene, it is clear that he is callous and indifferent to the feelings of others, even his real friends. He openly tells his date that being in a final club would let him introduce her to people “she couldn’t meet otherwise.” In addition, he readily manipulates Eduardo to get money to start Facebook, strings along the club members who give him the idea, and hacks the dormitories’ websites to start his first website. Much later in the film, there are even questions of whether he leaked a story about Eduardo to The Harvard Crimson and called the cops on Parker at a party where the latter is arrested for cocaine possession.

Ultimately, the treatment of Mark Zuckerberg strongly resembles Citizen Kane. In both films, the protagonist is a man obsessed with regaining something he lost, forgetting his friends, ethics, and other things that truly matter in the obsessive pursuit of his goal. The final scene even has Zuckerberg’s own “Rosebud.”

As for the technical components of the film, the narrative style is told in the present at two different depositions, one for Eduardo, and the other for the Vinklevoss’ (jokingly referred to at one point by Zuckerberg as the “Vinklevi”). For those not familiar with legal jargon, a deposition is essentially an interview that occurs under oath and (hopefully) with the witness’s lawyer present. It is during these moments where it becomes painfully obvious what a horrible person Zuckerberg would be to put on the stand. He is condescending to everyone in the room, giving off an arrogance that says “I am smarter than everyone here.” After a short question-and-backtalk session between plaintiff’s attorneys and Zuckerberg, the scene flashes back.

Meanwhile, Fincher maintains the filming techniques that he has used in so many movies, including his characteristic of putting a color filter over the camera lens. Further, just about every scene has little light in it, even during the middle of the day in California. The film is also full of Sorkin’s idiosyncrisies, including fast-paced witty banter and the classic “walk and talk.” If nothing else, Sorkin proves again that he knows how to write characters and dialogue very well, even if the narrative style can be a bit confusing when trying to figure out when the depositions are occurring in linear terms.

As I mentioned, the legal issues held a particular interest for me, and I think I was the only person who laughed when Divya Nerandra animatedly suggests suing Zuckerberg for stealing “their idea.” Having taken IP law last spring, the first thing you learn in that class is that you can’t sue someone for stealing an idea. It is only the actual product that can be in controversy, and near as I can tell, Zuckerberg is only guilty of lying about building a website. As the Vinklevoss’s pursue action against Zuckerberg, they get turned down by a Harvard Administrative Board and the president of the university for disciplinary action against Zuckerberg. Ultimately, as in real life, the matter is settled out of court, but there’s really nothing that is owed to them. An idea itself cannot be patented, copyrighted, or trademarked–it is only the product that holds these legal protections. Several times throughout the film, Zuckerberg claims that even though he saw their code, he didn’t use it. If he stole the code, this would be a different story, but creating his own code to run a similar site (to my knowledge) is not actionable. In my opinion, the plaintiffs get lucky off the fact that Zuckerberg would make for such a horrible witness.

Eduardo, on the other hand, was legitimately screwed, and both he and Sean Parker get what is coming to them.

Ultimately, this was a good film and is highly recommended. It acts as cultural marker for our generation. Certainly, those of us in our mid-to-late twenties and beyond will be the last ones to remember what life was like without Facebook, and even so, it feels like a distant memory. This film will remind you what it was like to get your first “friend request,” and one can only hope that somewhere, Mark Zuckerberg truly understands what it means to have friends.

Rating: 4.5/5

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy has this to say about John Rabon:

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy has this to say about John Rabon: