Cassavetes is not just a name, it’s a definition. When dedicated film lovers hear that word, they think independence, rebelliousness, and fearlessness. It means using your wits to accomplish your goal, never quitting, and believing that “no” really means “try harder.” John Cassavetes wasn’t the first independent filmmaker, but he is considered the quintessential American independent.

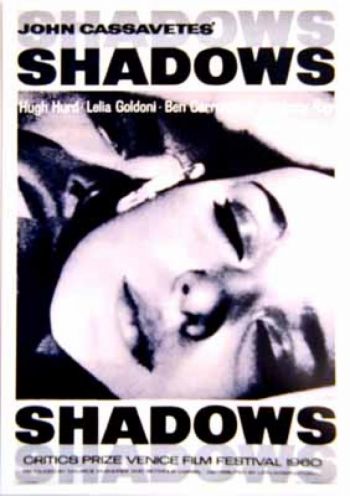

Filmmaker magazine voted his movie A Woman Under the Influence #1 on their list of The 50 Most Important Independent Films. Further, Cassavetes had more films named by the magazine’s poll respondents (Shadows, Faces, Killing of a Chinese Bookie, Love Streams, and Opening Night) than any other director. Rather than all of these films being included here, we will concentrate instead on Cassavetes’s directorial debut, Shadows. If any of you future filmmakers want to know how he did it, read on, noting that Cassavetes’s own observations are quoted.

The frenetic Cassavetes had been making a living as an actor in TV’s Golden Age (GE Theater, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Playhouse 90) and movies like Edge of the City (with Sidney Poitier) and Crime in the Streets (with Sal Mineo) when he became so frustrated and angry with corporate/studio control over art, and greed over creativity, that he turned to coaching. With his friend and colleague, Burt Lane (father of Diane Lane), Cassavetes founded an acting workshop in an effort to seek what author Phillip Lopate called “the fugitive truth.” Cassavetes believed strongly in having a story driven as it is in real life: by character, not plot. His unerring quest to find the truth of his characters became an obsession, beginning with his first film, Shadows. In his own words:

Shadows began as a dream in a New York loft on 13 January 1957. I dreamed up some characters that were close to the people in the class, and then I kept changing the situations and ages of the characters until we all began to function as those characters at any given moment. One particular improvisation exploded with life. It was about a black girl who passes for white. It was a basic melodramatic situation in which she was seduced by a young man, who then realized that she was colored. I chose a situation like this so that the actors would have something definite and emotional to react to. The wild dream grew that this improvisation could be captured on film. Until dawn that morning, the dreamers talked.

To realize his dream, Cassavetes used every all his energy, and every method at his command to raise funds, cajoling reluctant friends, taking acting jobs he hated just to earn money, lying, begging, borrowing. Instead of money for his often-inexperienced actors, and to assemble a reasonably knowledgeable technical crew, he promised bits of the movie in lieu of cash. In order to avoid the expense of permits from the City of New York, he shot night street scenes from inside restaurants through their plate glass windows. Luckily, one of the actors had a day job as a cabbie and parked his cab near the night shoots; as soon as the shoot was finished, the camera would be thrown into it and the cab would take off before the cops came. Sometimes cables would have to be run across streets or blocking walkways, and, besides no permits, they had no insurance. To deal with this, lookouts were posted to warn them in time for a quick getaway. They shot from rooftops or theater marquees, using a telephoto lens.

At the time of night shooting, Cassavetes’s wife, Gene Rowlands, was starring in a Broadway show, but she still managed to do two scenes in Shadows. The film credits a “collective improvisation.”

Lacking money for any fundraising publicity but needing to generate interest, Cassavetes made a plea for funds on Jean Shepherd’s popular radio show, Night People. For weeks after, those listeners who liked what they heard and wanted to be a part of it dropped off small sums of money at the Workshop. In Cassavetes’s own words:

One soldier showed up with five dollars after hitch hiking 300 miles to give it to us. And some really weird girl came in off the street; she had a mustache and hair on her legs and the hair on her head was matted with dirt and she wore a filthy polka-dot dress; she was really bad. After walking into the workshop, this girl got down on her knees, grabbed my pants and said, “I listened to your program last night. You are the Messiah.” Anyway, she became our sound editor and straightened out her life. In fact, a lot of people who worked on the film were people who were screwed up and got straightened out working with the rest of us. We wouldn’t take anything bigger than a five dollar bill, though once, when things looked real rough, we did cash a $100 check from Josh Logan.

Over the next two years, Jean Shepherd’s Night People made two more appeals for money, and Cassavetes secured more substantial donations ($100+) from the more affluent in show

business like William Wyler, Robert Rossen, and Reginald Rose. Even the noted thriftmeister and head of Delux Film Labs, Spyros Skouras, contributed film stock and allowed Cassavetes to use his lab for processing. Miles Davis was sought to provide a jazz score, but was unavailable at the time he was needed. Instead, Charlie Mingus’s jazz perfectly fit the rhythm of Cassavetes’s direction.

Shirley Clarke, who was working in those days as one of the few independent filmmakers, had the only equipment in town, so she brought it down and said, “Go ahead, make it. I’m not doing anything for six months. Take the equipment.” Other people brought in stuff. And they all contributed to this thing. People started building sets.

It didn’t matter to me whether or not Shadows would be any good; it just became a way of life where you got close to people and where you could hear ideas that weren’t full of $#&%. We had no intention of offering it for commercial distribution. It was an experiment all the way, and our main objective was just to learn. Not one actor was paid for his services, nor were the technicians given anything. What kept us going was enthusiasm. We were working for the fun of doing something we wanted to do. It is more important to work creatively than to make money. We would never have been able to finish if all the people who participated in the film hadn’t discovered one absolutely fundamental thing: that being an artist is nothing other than the desire, the insane wish, to express yourself completely, absolutely.

Loved or loathed, Cassavetes persevered, giving no quarter, and shooting was completed in May 1957. Editing the film, however, would take another year and a half. Imagine having 60,000 feet of film, without thinking about editing. No one had any editing experience and, even worse, much of the dialogue was so badly recorded, it couldn’t be used. The topper was that they hadn’t thought to keep a record of what had been said, so they couldn’t loop the dialog either.

When it was finished, we didn’t have enough money to print all the sound. There was no dialogue written down so every take was different. And most of the sound was incomprehensible. We looked at it and said, “What the hell are we going to print here? I don’t know what they’re saying. It looks terrific, everything’s all right, it’s beautiful — we’ll lay in the lines. We had a couple of secretaries who used to come up all the time and do transcripts for us. They volunteered their services to create a looping script, but they had nothing to do! We had all silent film. So we went to the deaf-mute place and we got lip readers. They “read” everything. It took us about a year just to figure out the dialogue and dub it in.

It took yet another year and a half, after which they couldn’t find anyone to distribute it. At a cost of $25,000 (more than three times what Cassavetes had estimated), the first screening was held. Cassavetes found that it was still not flawless, and it would be over a year and many added scenes and cuts later before Shadows would achieve the cult status it enjoys today. He had taken an improv workshop’s creativity and turned it into a first directorial effort that led to many more successful indie films, enough to make Cassavetes the inspiration of Martin Scorsese.

On September 19, 2009, Lincoln Center Film Society held a watershed retrospective of signature films from the world cinema’s most influential auteurs. Shadows was one of them. The Epoch Times wrote, “Every American filmmaker who ever told the Hollywood studios to stick it in their ear is a spiritual descendent of John Cassavetes.”