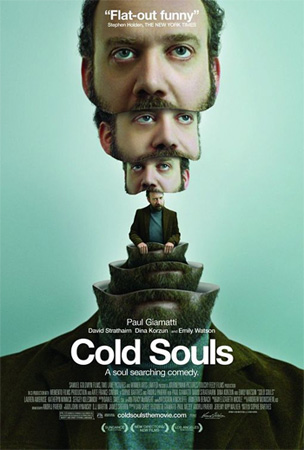

Review: Cold Souls

Director: Sophie Barthes

Writer: Sophie Barthes

Cast: Paul Giamatti, David Strathairn, Emily Watson, Katheryn Winnick

Rated: PG-13

This article contains spoilers for Cold Souls, Barney’s Version, and The Adjustment Bureau.

I’ve never seen Paul Giamatti give a bad performance in a movie. It’s entirely true that I’ve seen him in some questionable movies, but he’s never been anything less than excellent when he’s been on screen. He might be one of the best and most underrated actors around at the moment.

Giamatti is what we refer to in a vaguely insulting euphemistically way as a “character actor”. It’s a way of describing an actor (or actress) that can play almost any kind of role in any kind of film but just doesn’t have “the look” that’s needed in order to make that transition to be a full-fledged movie star. The opposite of this would be someone like Megan Fox who is allegedly quite good looking but has absolutely no talent, yet despite not having any talent was labeled as a movie star, though that star is thankfully now on the wane.

But in the past two months, I’ve seen two Giamatti movies that were shamefully disregarded when they were released in Irish cinemas but, when I finally got to see them in the comfort of my own home, totally blew me away (though they were two very different movies and they affected me for two very different reasons). The first one I saw was Barney’s Version, and I’ve been dying to see it ever since it was in the cinemas here. Due to having to work late most of the week, and the film only getting a run of about a week, I totally missed seeing it in the cinema. But as soon as it popped up on iTunes, I was all over it.

Barney’s didn’t disappoint at all. It was a brilliant movie about life and love and relationships, and maybe also about not really appreciating what you’ve got until it’s gone (the one thematic link it shares with Cold Souls). It was a well thought out, well scripted, superbly acted comedy drama that damn near broke my heart. Through a brilliant use of Old-Barney as a framing device, we see how Giamatti’s Barney began married life and how he ended and, most importantly, how he got from the beginning of his own story to the end. And when we got to the end of Barney’s story, we saw the tragedy of his life and the tragedy that the greatest tragedy in his life was of his own doing, but also got to see a mystery be resolved and Barney proved innocent for a crime that he never committed.

Cold Souls doesn’t quite have the same scope as Barney’s Version in terms of timeframe. It only chronicles one specific period in the life of the protagonist. The period is the time in his life when he decides that his soul is a burden and then subsequently decides that not having his soul is even more burdensome.

As mentioned earlier, Paul Giamatti is a character actor, and the character that he plays in Cold Souls is… Paul Giamatti. Well, Giamatti plays a certain version of himself in much the same manner that Adam West and James Woods play certain versions of themselves in Family Guy. The version of of himself that Paul Giamatti plays in the movie is a nervous, uncertain, doubt ridden man who finds it difficult in separating himself from the roles that he plays doesn’t feel that he is up to the part of playing the title role in Uncle Vanya. The role weighs on his soul, and obviously the best way to overcome this obstacle would be to get rid of his soul for an undetermined period of time.

One of the challenges of a movie like this isn’t actually the notion of a physical, tangible, removable soul that can be stored. It is a movie, after all. No, the challenge is accepting that the protagonist is so ready to accept that notion. One of my big problems with the Adjustment Bureau movie was the ease with which Matt Damon’s character was ready to accept that his destiny was not of his own making, that all of his life was preplanned and he had little or no choice in the course of his life. But then Emily Blunt would appear on screen again and I’d forget any problems that I had with the movie, just thinking instead “ooh, look at the pretty lady”.

In Cold Souls, Giamatti does need a certain amount of persuasion before undergoing the soul extraction process, but just in the way that any medical process is a big decision and sometimes we need someone to talk us in to doing something that we already know that we’re going to do. This task is performed by David Straithairn, who plays the Doctor who performs the initial extraction of Giamatti’s soul. Both Giamatti and Straithairn are fantastically talented actors and watching the two of them sitting in a room discussing soul removal in such a matter-of-fact way makes you want to believe that such a thing is possible. They make you want to believe that, if only for a little while, you could take all of the things that weigh you down, your worries and doubts and uncertainties and fears, and stick them in a glass jar where they can sit and be safe until you’re ready to bear that weight again.

So after one apparently routine soul extraction and storage procedure, Giamatti goes off and lives his life soul-free. The anguish that he felt from having to perform in Uncle Vanya is totally gone and he feels much easier about his role in the play and his role in his own life. But, as with most things in life, there is a darker side to this practice.

The facility where Giamatti went for the “procedure” also has a service whereby they can rent out souls for a period of time to the desouled. These souls-for-rent come through black market channels from Russia where the poor and the beleaguered are willing to give up something that they may not even ever have believed in in return for a cash payment, not knowing the consequences or risks.

It turns out that in order to play the part of Uncle Vanya, one does need some depth, some emotional base to draw upon. Basically one needs a soul, even if that soul is only a loaner. This is why we never saw Angelus play Uncle Vanya. After we see a Russian woman desperately trying to get her soul back from the black marketeers, Giamatti decides that renting a soul will help him to play Uncle Vanya without that aloofness that he brings to the role when he is without a soul. The soul that he decides to rent in order to make this happen (based on a very loose description) is the soul of a Russian poet. In fairness this isn’t a bad decision in isolation, there’s no one soul more qualified to connect with the role of Uncle Vanya than that of a Russian poet. And when we see the movie version of Giamatti act in the play while carrying the soul of the Russian poet, we’re shown again just what an amazing actor Giamatti is.

Renting a soul, though, is not without its own particular consequences, and Giamatti gets flashes in to the memory of the life that the soul lived before extraction. The soul is such a beautiful soul that he wants to meet the original donor. This is where things start to get complicated. At the head of every black market is a boss, and the wife of this particular boss wants the soul of an actor in order to help her in her acting career. She wanted Al Pacino, but Pacino’s soul is firmly in place inside Pacino so instead of Pacino, Giamatti’s soul is smuggled out of the storage facility and brought to Russia to be given to the boss-wife.

Sveta, the boss-wife, is played quite brilliantly by Canadian actress Katheryn Winnick who I have only ever seen in one other role before Cold Souls. That role was as a rape survivor in an episode of House, M.D. called “One Day, One Room”. It stands to this day as one of my favourite episodes of House and much of the reason behind that is due to the performance that Winnick gives in the episode.

Up to this point, Giamatti has been stymied in his desire to hunt down the donor of the soul-for-rent. He obviously feels that a soul like this is too good a thing to be sitting on a shelf or worse again, be sitting inside a stranger. He’s given the information on who the soul-mule was that brought the poet soul to America from Russia and it turns out that the mule, Nina, also has information on where his own soul is. So one plane flight later, we see Giamatti freezing his ass off in Russia trying to find a body with no soul and a soul in the wrong body.

It still amazes me that even movie-Giamatti doesn’t ever remark on the story-like quality of this adventure that he’s found himself on.

A soul is too precious a thing to be without and it seems that the poet donor realised this when she was told that retrieving her soul was an impossibility. We are shown that anything she did, she did for her family and the money that she was given in exchange for her soul all was spent on making life easier for the family that she cared for so much. She was willing to sacrifice everything that she had in order to try to make life a little bit better for her family. We have all at one stage or another in our lives thought that there is one person in the world that we can’t live without, but it turns out that the one person in the world that you can’t live without… is yourself.

After tracking down the poet, Giamatti, is naturally enough, pretty dismayed to find out that she has killed herself, obstensibly because she couldn’t bear to live without her soul. Upon this revelation, he takes the poet’s photo album. Maybe realising that photographs are the part of our soul that we share with the world.

After he realises that there’s nothing more to be done for the poet, Giamatti decides that it’s time to recover his own soul and put it back where it belongs. But in order to do that, he has to talk to Sveta’s husband who is less than inclined to return that soul as Sveta’s acting has improved dramatically. Though it turns out that she’s acting in a Russian soap opera which freaks Giamatti out fiercely. When Sveta’s husband refuses to help with the extraction of the not-Al Pacino soul, Nina and Giamatti decide to go straight to Sveta and tell her what’s happened. But much to everyone’s surprise, Sveta seems very happy with her life and content with her acting while carrying the soul. What she’s not happy about though is being lied to about the soul’s identity by her husband. So Nina and Giamatti decide that the best thing to do is be at an event where Sveta will get drunk and pass out, allowing them to “borrow” her and remove the soul from her.

Due to the amount of time that the soul in storage and then in Sveta, Giamatti finds it hard to reconnect with his own soul. They’d both been through too much at that stage and had become almost strangers in a way. The only way for the soul and the mind to be able to reconnect is for Giamatti to take a look inside his own soul for the first time and see exactly what it was that made him the man he had been.

After reconnecting, Giamatti seems happier with his life. It’s not entirely clear if it’s just relief at being whole once more, if it’s realising that you don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone, or if it’s just the effect on the soul that Sveta had while she carried it. The happiness and contentment with her life and her job could have left an impression on Giamatti’s soul.

The “real” Paul Giamatti is a brilliant actor who can carry pretty much any film on his back. Hell, he even made Lady in The Water watchable. Both Barney’s Version and Cold Souls were worthy vehicles for him, but they are two movies that affected me very differently. It’s not hard for a movie to move me like Barney’s Version did, in fact it’s almost embarrassingly easy. But it’s a rare thing for a movie to make me think the way Cold Souls did.

Anyone who knows me will tell you unreservedly that I’m not a religious man, I don’t believe in heaven or hell. It’s all fairytales and unicorns to me. But the idea of a physical, tangible, removable soul is one that I find fascinating. The idea that the core of who we are can exist independently from our weak, degenerating bodies opens up a myriad of possibilities.

And now, I kinda want to see what it’s like to have the soul of a Russian poet.

Simon FitzGerald isn't your average Irishman. He has an unhealthy addiction to TV, movies and comic books and uses the word "awesome" far too much Though he does enjoy a pint as much as the average Irishman.

Simon FitzGerald isn't your average Irishman. He has an unhealthy addiction to TV, movies and comic books and uses the word "awesome" far too much Though he does enjoy a pint as much as the average Irishman.