A couple of years ago, Greg Davies over at Geeks of Doom wrote an article about the inevitability of a fourth Matrix film, and much to the chagrin of formerly skeptical fans we recently spent a few days thinking that Davies not only was correct in his assertions about the franchise, but that we would be treated to two additional Matrix films (recent confirmation by “The One” himself, Keanu Reeves, turned out to be nothing more than speculation and rumors). In an article published just this week, Davies cites the release of Tron: Legacy, the long-awaited sequel to a movie that was one of the many influences behind The Matrix, as well as the advances in 3-D filming techniques made by James Cameron in recent years as reasons why this would be the perfect time for the Wachowski brothers to jump-start the Matrix saga.

Once again it looks as though Davies may have hit the nail on the head with his analysis of the Matrix franchise, and I find myself not only agreeing with his well-reasoned points about timing and technology, but also with the slight hint of disdain evident in the overall tone of his article. Davies’s point about the profitability of the Matrix films does not fall on deaf ears — while the Wachowski brothers may be creative and successful enough to earn some leeway when it comes to the motivation behind the (now debunked) resumption of the Matrix series, there is no doubt that the Matrix narrative would not continue had the franchise not broken box office records and raked in loads of dough with its various merchandising techniques.

The rumors that the Wachowski brothers planned to release an additional two Matrix films are much more significant than other similar decisions recently made in the film industry. Although the decision could be heralded as more evidence that filmmakers never know when to quit (see Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull), it also signals that the concept of media convergence, and subsequently convergence culture, is as alive and well today as it was in the late 1990s. As former Director of Comparative Media Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Henry Jenkins points out in his book, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, The Matrix is a hallmark example of entertainment designed specifically for the age of media convergence: it was the first film franchise to provide a narrative so large that it could not be contained within a single medium.

Even before The Matrix was released in 1999, its advertising campaign drove viewers to the Web in search of answers to the question “What is the Matrix?”. As the film played with viewers’ concepts of reality and perception, message boards and online communities cropped up with the hope of “truly understanding” the concept of “the Matrix”. As casual and fanatical Matrix fans alike can attest, the skimpy recap provided at the beginning of the first sequel, The Matrix Reloaded (2003), and the movie’s cliffhanger ending, which promises that everything will make sense with the release of the third installment, The Matrix Revolutions (2003), are evidence of the level of dedication required to comprehend the series’s complex storyline and follow its extensive cast of characters.

As Jenkins points out, the Matrix narrative requires viewers to do their homework: the movies are riddled with “clues” that won’t make sense without playing the computer game. Similarly, these clues rely on information that can only be obtained by watching a series of animated shorts initially available only via download on the Web but later released on DVD . The media convergence displayed and required by the Matrix franchise is best summed up in the author’s own words, however, when he writes:

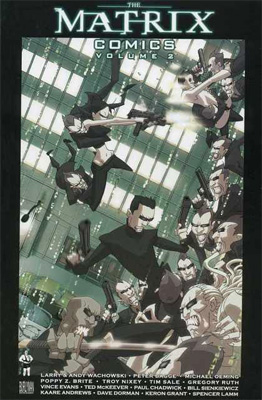

The Wachowski brothers played the transmedia game very well, putting out the original film first to stimulate interest, offering up a few Web comics to sustain the hard-core fan’s hunger for more information, launching the anime in anticipation of the second film, releasing the computer game alongside it to surf the publicity, bringing the whole cycle to conclusion with The Matrix Revolutions, and then turning the whole mythology over to the players of the massively multiplayer online game.

The concept of a “transmedia” story presented by Jenkins in Convergence Culture is actually a very simple one: a story that unfolds across multiple media platforms, each component of which provides new and unique additions to the narrative as a whole, is considered to be a “transmedia” narrative, and The Matrix and its counterparts (which now range from online communities and fanfic to graphic novels, as well as the previously released movies and games) compose what is arguably the most poignant example of this practice in recent times.

It’s easy for moviegoers to overlook or minimize the influence of The Matrix, as transmedia narratives are often taken for granted these days due to the fact that production and release of supplemental texts has become a more common practice among television shows and film franchises. Popular series like the BBC’s Doctor Who and Torchwood have stepped onto the transmedia platform, boasting myriad books, graphic novels, and even online multiplayer computer games that expand upon the narrative arcs provided in the television episodes, but these franchises are fundamentally different from the Wachowski brothers’ creation. The Matrix remains a significant landmark in media history because of the intentional way that its various components were planned and executed. Even if it were not one of the best examples of modern convergence culture in action, the Wachowski brothers’ films also pioneered groundbreaking techniques in camerawork and special effects that will not soon be forgotten in the film industry, and which heighten the anticipation of many viewers now that the Wachowskis have the opportunity to build upon James Cameron’s advances in 3-D filming techniques.

Personally, I enjoyed The Matrix a great deal, but lost interest in the series after viewing each of the sequels a couple times. Like many other contemporary film enthusiasts, I shook my head and heaved a sigh when I first heard that Keanu had confirmed plans for two additional films, immediately assuming that neither will be able to live up to the groundbreaking, adrenaline-inducing greatness of the original movie. The fact that ill-conceived, poorly written sequels to famous films are routinely green-lit in Hollywood has left me jaded when it comes to even theoretical discussions about rebooting popular film franchises, and the Matrix movies are no exception. Even in the event that more Matrix films never come to fruition (after all, the fact that Keanu Reeves’s reps dispelled the rumors shortly after they began to circulate doesn’t mean that the Matrix narrative will never be continued), it is undeniable that the franchise has made a lasting impression on media integration, entertainment, and the commercialization of convergence culture and that it continues to provide us with a platform on which to examine various aspects of popular culture and collective intelligence.