High Fantasy is probably one of the most recognizable subgenres of Fantasy. It may go by a few names — Epic Fantasy or the Hero’s Quest — but in the end most people can name at least a series or two from this subgenre. However, just because it is recognizable doesn’t mean that it shouldn’t be defined in more depth; as a subgenre it has interesting nuances and is evolving in some ways while still remaining true to itself. After a long break I thought it was only right to bring back Defining the Genre with high fantasy.

Definition

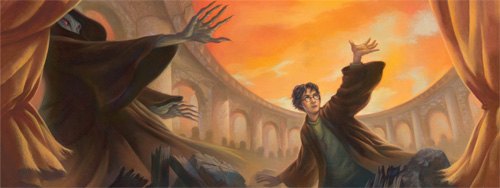

Often also called Epic Fantasy or the Hero’s Quest, these are stories that most fans of fantasy have read at some point or another. While high fantasy can look and feel very different depending on the author, you will find certain aspects are nearly always the same. As mentioned, there is a hero, sometimes of humble origins, who must rise above his or her circumstances and is compelled to act by conditions and/or events outside of their control. We see this character grow up and become someone great, defeat the odds, and challenge the evil and corrupt. The hero may not always succeed at first try, but they will find means either within themselves or from outside sources to continue on their quest, which if they fail, would have world-reaching consequences.

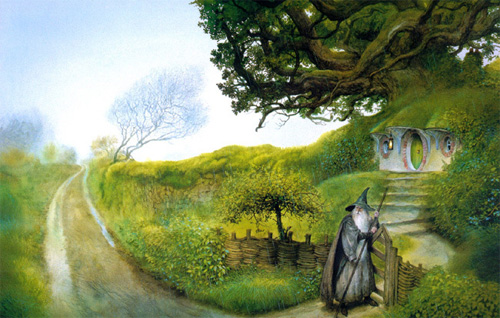

The settings for these quests are generally in one of three varieties: a world separate unto our world, one where our world for all intents and purposes doesn’t even exist; a secondary world that is reached from our world through a portal; or, lastly, a secondary world within our own world. Tolkien’s Lord of The Rings and Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series are examples of the first variety. They both exist in a completely developed secondary world that is not Earth — Earth doesn’t even exist in their minds. The Chronicles of Narnia is a classic example of a portal into another world variety and the Harry Potter series is a contemporary example of the “world within a world” type of high fantasy.

The story is usually told through the eyes of the main character, or hero, and follows them nearly exclusively while supporting characters can come or go. The hero is leading the charge for the “good guys” against the evil that is threatening to take over and ruin the peace. I’ve been trying to avoid gender pronouns, but high fantasy also has the characteristic of being fairly male-centric, in protagonist, in authorship and often in readership, although this is not always the case, but there is definitely a more masculine emphasis. High fantasy can also be characterized, although this is not always the case by being a series, with episodic installments.

Origin

Much like the Fairytale previously discussed in Defining the Genre, high fantasy is often based on myth or legend. We recognize all of the ingredients of high fantasy is stories such as Le Morte d’Arthur, or the story of Arthur, Camelot and the search for the Holy Grail, a legend of Welsh origin. It is a hero’s tale — Arthur, who has no control over whether or not he can pull a sword from a stone or not, does, and suddenly kingship is thrust upon him. Matters beyond him and magic turn his life, which would have been otherwise dull and ordinary, into the stuff of legend.

Creation stories, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, are epic fantasy. Echoes of these stories have been passed down through the ages and were at one point rooted in local myth, tradition, lore, or legend. Hercules had 12 Labors he had to perform, many of killing mystical beasts and dealing with Gods. These stories still stir imaginations today and influence epic literature by their fantastical nature. High fantasy has roots as far back as fairy tale; they are human stories passed down, aggrandized and lasting.

Many high fantasy stories we are familiar with today can tip a hat to the Arthur legend, one of the most recognizable being The Lord of the Rings. Take, for example, the idea of Merlin as a magical man, a wizard. He can easily be seen as the predecessor to Gandalf. While The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are among the most famous high fantasy novels, and perhaps even brought the genre a significant amount of attention, it would be impossible not to mention The King of Elfland’s Daughter by Lord Dunsany. This story is a classic from 1924 that was published before the genre was even named.

Evolution of High Fantasy

In the game of good versus evil, there have been many players. In more recent fiction, we’ve seen adaptation and evolution within the genre. A prime and popular example of such a shift is The Dark Tower series by Stephen King. Roland Deschain cannot be described as a hero in the classical sense; he’s an antihero. He’s rough around the edges, has a haunted past, and isn’t afraid to do what must be done to achieve his goal, even if innocents must die in the process. His tale is no less high fantasy, however; he pulls characters through portals into his world, they are there beyond their control, and they must go on a journey to rid the world of the evil that has taken over the Dark Tower. Roland may be acting on the “good” side, but he’s not a “good” character even if he does grow in that direction as the story progresses.

As we see with the Harry Potter series, it is possible to bring high fantasy into a more modern setting (and again remember that fantasy subgenres are not mutually exclusive as you could also classify the series as contemporary fantasy or even urban fantasy, although to a lesser extent). In the past the trope for high fantasy was that it was a medieval type setting with corresponding technology. While it could be argued that the higher level of technology you have in the story the closer to science fiction it may appear, I would argue that if the focus isn’t on the tech and how the tech affects the world, but rather how fantasy and the fantastical elements affect the world, it will be possible to stay true to the heart of high fantasy.

Reading List

- A Song of Ice and Fire by George R. R. Martin

- The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

- Mistborn Trilogy by Brandon Sanderson

- The Book of Three by Lloyd Alexander

- The Once and Future King by T.H. White

- The King of Elfland’s Daughter by Lord Dunsany

- The Darkness That Comes Before by R. Scott Bakker

- The Last Unicorn by Peter S. Beagle

- Lord Foul’s Bane and The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant series by Stephen R. Donaldson

- A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin

Resources

- Gamble, Nikki; Yates, Sally (2008). Exploring Children’s Literature. SAGE Publications Ltd. pp. 102–103.

- William, Charles. Welsh Celtic myth in modern fantasy. 35. Greenwood Pub Group, 1989. Print.

- Wynn, Judith. Some of My Best Friends Are Books: Guiding Gifted Readers from Preschool to High School. 3rd ed. Great Potential Press, 2009. pp 221

After thirty years of reading, writing and researching the fantasy genre, I’ve recently started a blog on the subject. My first series of posts will be about High Fantasy stories and the Medieval Model.

What is this model you ask. While Joseph Campbell had his monomyth of the Hero’s Journey to explain the structure of myths and epic tales, C.S. Lewis had his “Medieval Model” to explain the textures, colors and flavors of the stories from the Middle Ages and Renaissance. When you hear a professor of Medieval literature recommend the novels of Lewis or Tolkien as a good introduction to Medieval literature for modern readers, it is the elements of the “Medieval Model” found in these tales that they are referring to. While it is Lewis and Tolkien’s mastery of their craft that allows them to bring these elements successfully into stories that the modern reader enjoys, in reality these elements are timeless and speak to the inmost needs of our hearts.

To help illustrate the elements of this model in High Fantasy novels, I contrast High Fantasy with the genre that often seems to be its mirror image, namely Hard Sci-Fi (so even if your tastes run more towards sci-fi rather than fantasy, I would still appreciate your thoughts and comments on the blog, even if simply to see that I represent your favorite genre correctly).

Here’s my blog’s URL: http://theswordoffire.wordpress.com/

Please drop by, read a bit and leave a comment.

Regards,

Bill McGrath

Actually, according to Tolkien himself in one of his interviews with BBC, the whole Tolkien Legendarium is set in an alternate past history of this world. It can be seen in the maps of the continent of Middle-earth. It is actually the supercontinent of Pangea. It would be great if the misconception of Tolkien’s work falling under the first group in the High Fantasy genre, its setting being in another universe, should be revised and corrected. This is the actual quote from the transcript linked bellow:

“D. Gerrolt:: I thought that conceivably Midgard might be Middle-earth or have some connection?

J.R.R. Tolkien: Oh yes, they’re the same word. Most people have made this mistake of thinking Middle-earth is a particular kind of earth or is another planet of the science fiction sort but it’s just an old fashioned word for this world we live in, as imagined surrounded by the Ocean.

D. Gerrolt: It seemed to me that Middle-earth was in a sense, as you say, this world we live in, but this world we live in at a different era.

J.R.R. Tolkien: No … at a different stage of imagination … yes.”

Links of the mentioned Interview and authorized transcript:

https://youtu.be/9-G_v6-u3hg

http://www.tolkienlibrary.com/press/804-Tolkien-1971-BBC-Interview.php