With Watchmen, the “unfilmable graphic novel,” now in theaters, it’s time to take a look at the last Alan Moore work that was brought to the big screen — the politically-laced graphic novel, V for Vendetta.

Like every prior adaptation of an Alan Moore graphic novel (each disavowed by the writer himself), V for Vendetta was taken on by the Wachowski Brothers (of Matrix fame) to adapt to the silver screen. This was a daunting endeavor, as prior Moore works (From Hell and League of Extraordinary Gentlemen), had their own shares of issues with novel-to-film adaptation. Though several adjustments were made to the story, the heart of V for Vendetta remained intact when brought to film.

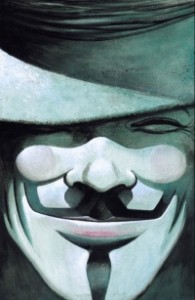

The story of V for Vendetta surrounds a man who works to arouse the masses against an oppressive government. Some see him as a terrorist, some as a revolutionary. In his journey, he meets a young woman who he inspires from the ashes to take on his cause after he can no longer. This of course, is a very brief synopsis of the story, which has much more meat on its bones to enjoy.

The graphic novel was written at a time when Margaret Thatcher was in office, and essentially written as a testament against her run of government. The novel tells of a war (assumed to be World War Three), which nearly transforms England into a state of Anarchy and eventual Fascist governments. While the film keeps this notion of post-war existence, it is aimed more at an anti-Bush viewpoint. This would likely be due to the time the film came out (2006), and the political atmosphere then.

A major adjustment to the storyline is V’s ambitions. In the novel, he openly acknowledges that his new “love” is anarchy and not justice. This is stated just prior to him blowing up the Old Bailey. His desire is to inspire just one to carry on his cause, not to inspire the masses to rise against their government. The film instead has V working to inspire all, and not the individual. The cause is much more grand, and the ending (with all those, dead and alive, dressed as V), shows a higher connection of people in their belief that many can do much more. The book leaves less of this feeling, and more of just an individual with an idea.

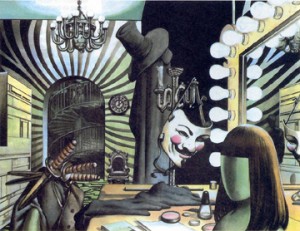

Another major difference from graphic novel to film is the characterizations of the major players. Though their names, actions, and sometimes looks are exact replications of the book, most of their personalities are considerably adjusted. The biggest differences are found in the leads: Evey and V. Evey was changed from a lost sixteen-year-old with little to no education to a strong-willed twenty-something with a good job and a moderate sense of self. Though the film variation of Evey isn’t one to rise up against the government, she still had the seed already planted in her head from her parents (who, in the film, were political activists later black-bagged). In the graphic novel, she is a lost soul with no ambition, just a weak will to survive (even to the point of prostitution). V, on the other hand, was changed from practically a doll-like man to someone as common and easygoing as anyone else. The V in the graphic novel does not watch movies, wear a pink apron while cooking breakfast, or play-fight against a suit of armor. He has lost all humanity, and is just the remainder of what once was. V in the film appears more as a caricature of a person, someone bigger than any one average person, just as his message would be.

The film especially excels in one way when it comes to adaption, and that is in showing the horrors of a totalitarian government, and what it is capable of against its own people. The original notions of the St. Mary’s virus (used against the country’s own populous in order to instill fear), black bagging anyone considered deviant, and absolute control over all forms of media are all excellent ways of showing just how frightening, yet realistically shown, this government is. The government in the novel, though just as frightening, retains a thin layer of human nature flowing behind its evils. This is absent in the film… thus making the government all the more inhuman and monstrous.

The order of events roughly stays the same from book to film, with minor switching around of key moments (i.e. blowing up of Parliament), and additional scenes being added into the story (to support the revised timeline and motives in the film). I will say that any scene that is in the book is very well recreated for the screen — especially the sequences involving Evey’s false imprisonment.

Overall the transition to film leaves much out that is key to the graphic novel, and adds in what works better on screen. The purists may dislike these changes (and I’ve met a few), but many who saw the film first and later read the novel found the film much more uplifting and effective. Either way, both the book and film are excellent in their own right, each telling the same story, but in two entirely different ways.

The next Adaptation Anaylsis will be the first to involve a stage-to-screen production. With the popularity of musicals now, it’s about time to do an anaylsis on one of the most famous musicals of all time, Phantom of the Opera!