Fairy tales have been told in every language in every country for as long as humans have allowed themselves to step into the realm of the fantastic. Given how recognizable fairy tales are, it may seem strange that I need to even take the time to define it at all, but I wanted to take some time to discuss the themes and reasons for why fairy tales exist. Perhaps the first answer that pops into your head is “to entertain children,” but that is only the tip of the iceberg.

When you hear the phrase “fairy tale,” certain names and images come to mind, from Disney to the Brothers Grimm. Some will think of stories like Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, and The Little Mermaid. Some stories have helpful animals, evil stepmothers, or enchanted forests yet, as different as these fairy tales can be, they often have a very similar tale. The hero starts out small and oppressed and, often with the help of a fairy godmother or magical item, must prevail against an all-encompassing evil. Let’s not forget winning the day and getting the reward, which is often portrayed as a promotion in social rank like becoming a princess. Even then, there is a current in fairy tales that runs deeper than that which this quick summary suggests.

Many fairy tales, like fables and parables, will often seem to have a moral message to them. However, as Sheldon Cashdan points out in his book The Witch Must Die: The Hidden Meaning of Fairy Tales, if you want the morality, look towards the latter two and not the former. Fairy tales have a darker, deeper undercurrent to them, a more psychological purpose. The stories often show children in difficult if not horrifying situations which they must overcome, inner conflicts they must deal with, and sacrifices they must make. The witch embodies the inner turmoil just as much as it does the physical obstacle that must be overcome.

Fairy tales continue to fascinate because they are more than just an enchanting story for children. What other children’s stories would use themes of cannibalism, abandonment, withholding of love and, if one reads the non-Disney versions, even rape and incest? In the first telling of The Sleeping Beauty by Giambattista Basile in 1634, the prince doesn’t kiss the sleeping maiden and cause her to wake — rather, he ravishes her, leaves her pregnant and returns later. And he isn’t entirely charming either (even aside from rape of a defenseless maiden), since he was already married (Cashdan, 22-23). Disney has retooled it so that it is almost completely different from its original telling, but in one form or another the story persists.

Fairy tales also can be quite confusing. We’ve all heard of “the fairy tale ending,” yet not all fairy tales do end “happily ever after.” There is often death and violence, and while that is often to characters on the periphery of the story, the main characters aren’t always exempt from heartache. If one reads Hans Christian Anderson’s The Little Mermaid, the happy ending (as we expect) isn’t in evidence. The Prince marries another princess, and the Little Mermaid is left to die. This is, of course, after she makes a deal to have her tongue cut out to become human. The story goes that the Little Mermaid is given the chance to return as a mermaid by her sisters’ sacrifices, but to do so she will have to kill the prince she loves. When she cannot, at dawn she dives into the ocean and becomes foam. Not the story many of us grew up with.

Overall, the Fairy Tale mirrors what we deal with as children. Our lives begin (one would hope) in a loving and warm, simple and secure environment. Little Red Riding Hood had a mother who cared for her when she was told to stay out of the woods, but her own curiosity got the better of her and made her life more complicated. As a child, Snow White lived happily with her father, but when she acquired a new step-mother, there was now conflict and competition for her father’s affection. Life starts out simple and gets complicated, and fairy tales are the analogy for how each child must in his or her own way face the new evils and hardships that threaten them as they age.

There is more to a fairy tale than meets the eye. While they can certainly be looked at as a simple story told to children, I think there is a deeper reason why we latch on to them. Even though in many ways they may be fantastical, they can still be connected with and related to. The study of Fairy Tales is a study into our own psychology. They are not just about the hero saving the day, but the hero becoming a better person by dealing with their own inadequacies and maturing from a simple child into a complicated adult.

Fairy Tales from Around the World (Recommended Reading):

- The Little Mermaid by Hans Christian Anderson

- Russian Fairy Tales

by Aleksandr Afanasev

- The Little Prince

Antoine de Saint-Exupery

- The Witch Must Die: The Hidden Meaning Of Fairy Tales

by Sheldon Cashdan

- Journey to the West: The Monkey King’s Amazing Adventures

by Wu Cheng’en

- Popular Tales of the West Highlands

by J. F. Campbell

- The Complete Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault

- Briar Rose

by Robert Coover

- Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister: A Novel

by Gregory Maguire

Art Used:

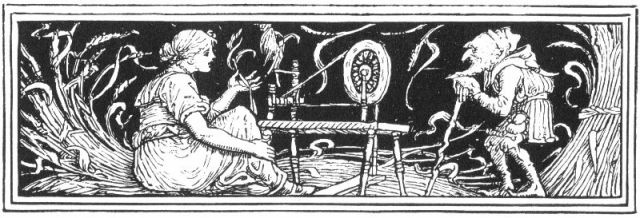

- Illustration of Rumpelstiltskin from Household Stories by the Brothers Grimm by Walter Crane, 1886

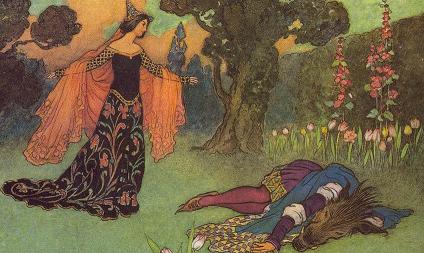

- An illustration by Warwick Goble for Beauty and the Beast, 1913.

this adds a whole new dimension I never thought was there. Thank you

I wanted this article to continue! I’m very interested with your theories about the psychology of fairy tales!